WEBINAR: DO WE NEED A BOARD? SUMMARY AND KEY TAKEAWAYS

Do We Need a Board? | Special Webinar on Arts & Not-for-Profit Governance

SUMMARY

Webinar delivered 28th August 2025

This webinar, hosted by David Fishel and featuring Heather Watson and Steven Bowman, examined the provocative question: “Do We Need a Board?” It explored whether boards truly add value in not-for-profit organisations and what alternatives or improvements might exist.

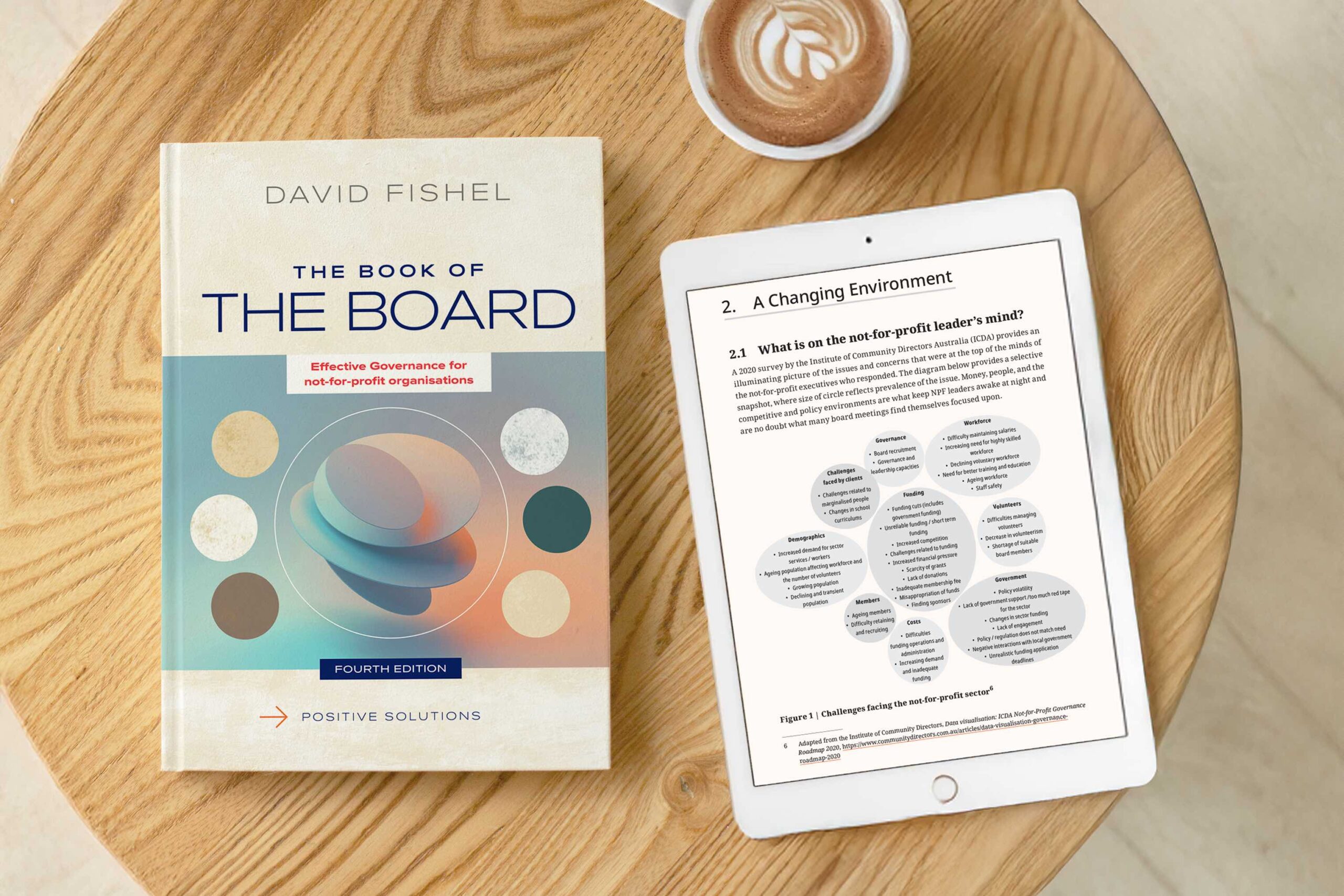

David Fishel began by outlining the background. When he first wrote The Book of the Board two decades ago, little guidance existed for non-executive directors. Today, organisations like AICD and the Institute of Community Directors provide extensive resources, yet problems remain: blurred roles between boards and management, directors uncertain about responsibilities, and CEOs unclear on how to best work with boards. This raises the issue of whether current governance models remain adequate, or whether new models or refreshed learning are needed.

Heather Watson argued strongly that boards do add value. She noted that while some organisations, such as government agencies and private companies, operate without boards, they often replicate collective decision-making through committees or advisory groups. In highly regulated fields like health and aged care, boards are essential to safeguard vulnerable communities. Beyond compliance, boards’ strategic role is critical, as they often hold the long-term vision when executive turnover is high. Heather emphasised that board value is most evident during crises: she recalled chairing a major aged care provider during COVID-19, where board confidence, collaboration with executives, and resilience were crucial to navigating uncertainty.

Steven Bowman challenged assumptions, recalling that many not-for-profits begin as informal associations, energised by passion and free from egos. Incorporation and the establishment of boards can sometimes dampen this spirit. He argued that structures such as constitutions, strategic plans, and risk frameworks are useful, but their success depends entirely on people. Boards succeed or fail because of dynamics, personalities, and behaviour. Bowman highlighted poor induction and inadequate mentoring as weaknesses, and urged boards to address disruptive behaviour immediately rather than tolerating it. Too often, he said, boards are “too polite” and allow dysfunction to persist.

Discussion turned to the “return on investment” of boards. Heather noted that boards should recognise their costs—not only director participation but also the staff resources needed to support them. Board size should be “fit for purpose,” and remuneration, where used, demands even greater accountability. Evaluation is key: boards should subject themselves to the same performance rigor expected of executives, ideally through collaborative frameworks. Bowman described helping boards identify KPIs that measure outcomes rather than activity, noting that boards often mistake busyness for value. Real impact comes from focusing on whether outcomes are achieved and whether boards are positioning the organisation for the future.

The conversation explored alternatives to traditional boards. Advisory boards, community panels, and specialist committees can add significant value, particularly when composed of non-directors. However, they must be set up with clear terms of reference. Umbrella structures may also reduce the proliferation of small boards competing for directors. Both Heather and Steven stressed that governance structures must be flexible and adapted to context.

Recruitment and succession emerged as major themes. Reliance on personal networks limits diversity and capability. Boards should advertise positions, maintain pools of potential candidates, and use committees as stepping-stones for prospective directors. Behavioural fit is as important as technical skills: interviewing and shortlisting processes should assess collaboration, humility, and capacity to engage with complexity. Induction must go beyond documents to long-term orientation and mentoring.

The role of the chair and the board–CEO relationship was highlighted as central. Boards must regularly meet without the CEO to build internal strength. Clarity and trust between chair and CEO underpin effective governance. The conversation also examined whether CEOs should be board members, with most participants favouring separation for clarity. Regarding CEO contracts, Heather and Steven agreed that both fixed-term and open-ended arrangements can work, provided performance is reviewed rigorously and culture supports accountability.

The session concluded with reflections on board assessment. Common tools include annual self-assessments, independent reviews, and 360-degree feedback. However, Bowman criticised surveys that generate no change. More valuable is honest reflection, stakeholder input, and constructive peer feedback framed as “insights” rather than criticism. Heather argued that mature boards must cultivate trust to engage in such feedback.

Key insights included the need for boards to dedicate time to long-term strategy and future-oriented stakeholder engagement, not just short-term compliance or financial pressures. As Bowman put it, the role of any board is “to make the choices that create the future for the communities we serve.”

In closing, the panel agreed that boards are not always necessary, and alternatives exist. Yet where boards operate, their effectiveness depends less on formal structures than on people, relationships, and purpose. Boards must continually refresh themselves, measure outcomes not activity, and balance structure with the passion that drives change. Their greatest value lies in helping organisations stay true to mission while preparing for an uncertain future.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

1. Boards add greatest value during times of crisis, providing stability, confidence, and leadership.

2. The strategic role of boards is essential, particularly in holding the long-term vision when executive turnover is high. Boards must dedicate time to long-term strategy and stakeholder engagement, not just compliance or finances.

3. Governance effectiveness depends more on people, behaviour, and relationships than on policies and frameworks.

4. Induction and mentoring of new directors are often weak and must be strengthened to build capacity.

5. Poor behaviour must be addressed immediately; being “too polite” allows dysfunction to persist.

6. Boards should measure their own value through outcomes, not activity or busyness.

7. Boards should experiment with collaborative performance frameworks that apply equally to directors and executives.

8. The costs of boards, including staff support, must be recognised; boards should be “fit for purpose” in size and structure.

9. Meeting frequency should be tailored to organisational needs; monthly meetings are rarely necessary.

10. Advisory boards, committees, and umbrella structures can provide effective alternatives or complements to boards.

11. Board Committees do not need to be dominated by directors; involving community members brings fresh perspectives.

12. Umbrella or federated models could reduce duplication and the struggle to find enough board members.

13. Recruitment must go beyond personal networks, focusing also on behavioural fit as well as skills.

14. The chair–CEO relationship is pivotal; boards should also meet independently of management.

15. Board self-assessment and independent review are essential, using honest reflection and stakeholder input.

16. Governance training and development need continual refreshing due to turnover and loss of corporate memory.

17. Remuneration for directors increases the importance of demonstrating return on investment.

18. Ultimately, boards exist to make choices that create the future for the communities they serve.